Black & White Luminaries: Insights into Adams and Garrett

Written By: SUSANNE LOMATCH

Those of us driven to black & white photography as a medium and fine art form can

usually point to established practitioners and a specific set of their creations as

progenitors of our own creative process. Ansel Adams and John Garrett are two pioneers

that roused my curiosities and motivated me to pursue this most abstract photography

form. Though I can cite a few known works that had the greatest impact on me, I had

never attempted (until now) to understand what either artist was thinking when he created

them. In this article I briefly discuss those inspirational pieces and the artist’s story

behind them, as is available in the published literature.

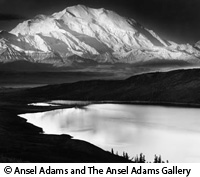

I start with Adams’ "Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake (c1947)." This image perhaps

made the greatest impression on me of all Adams’ works. Sharp contrast makes a bold

statement. Though the sky is quite dark, it has an almost unnatural tonal range compared

to the landscape, creating an effect of the mountain and sky hovering over the dark

outline of a lake. From Adams’ description [1], the photo was shot at 1:30AM in July; at

midnight there is always light – "a calm dusk of silence and wilderness." Adams shot the

scene near sunrise, just as the peak turned pink. He debated using a red #25A filter, but

settled on a deep yellow #15 instead, which adequately suppressed the shadowed

foreground to highlight the mountain and sky. He shot a total of three 8x10 images on

Isopan 64 before clouds enveloped the mountain at 2AM. Later, while traveling in

Glacier, he lost two of the three image negatives from the water damage sustained when

his film case dropped into the water during a float plane egress. On his recollection of the

Alaska trip, he noted that he preferred the original Indian name Denali, commenting "it

[is] a chauvinistic character of our nation to attach political names, quite often

insignificant in history, to the glorious features of the land." At the time, Native

American designations were a minority on maps. Adams was equally critical of Alaskan

mosquitoes, which had gotten trapped in his camera bellows in such numbers that a few

got stuck on the film – and appeared as "silhouettes of airplanes in the skies of some

negatives!"

I start with Adams’ "Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake (c1947)." This image perhaps

made the greatest impression on me of all Adams’ works. Sharp contrast makes a bold

statement. Though the sky is quite dark, it has an almost unnatural tonal range compared

to the landscape, creating an effect of the mountain and sky hovering over the dark

outline of a lake. From Adams’ description [1], the photo was shot at 1:30AM in July; at

midnight there is always light – "a calm dusk of silence and wilderness." Adams shot the

scene near sunrise, just as the peak turned pink. He debated using a red #25A filter, but

settled on a deep yellow #15 instead, which adequately suppressed the shadowed

foreground to highlight the mountain and sky. He shot a total of three 8x10 images on

Isopan 64 before clouds enveloped the mountain at 2AM. Later, while traveling in

Glacier, he lost two of the three image negatives from the water damage sustained when

his film case dropped into the water during a float plane egress. On his recollection of the

Alaska trip, he noted that he preferred the original Indian name Denali, commenting "it

[is] a chauvinistic character of our nation to attach political names, quite often

insignificant in history, to the glorious features of the land." At the time, Native

American designations were a minority on maps. Adams was equally critical of Alaskan

mosquitoes, which had gotten trapped in his camera bellows in such numbers that a few

got stuck on the film – and appeared as "silhouettes of airplanes in the skies of some

negatives!"

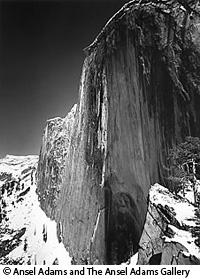

"Monolith: The Face of Half Dome (c1927)" is an early predecessor to Adams’ more

polished and famous Yosemite works, "Clearing Winter Storm (c1940)" and "Moon and

Half Dome (c1960)." All three have compelling narratives from Adams’ point of view,

and form a progression of his creative process. "Monolith" is raw and evocative, and if I

had to choose, my favorite of the three. It is the first photograph in which Adams

successfully utilized a deep red #29 Wratten filter to blacken a bland sky and push the

contrast limits, taking advantage of a recent snowstorm and afternoon sun-induced

shadows. Adams reminisces about the 2500 ft. steep climb he made that day with his

fiancée and friends. He shot a total of twelve Wratten Panchromatic glass plates during

the climb, and was left with two when he turned to face the Half Dome at a famous high

ledge. Not satisfied with his first exposure, Adams prepared for his final. "I realized that

the image would not carry the qualities I was aware of when I made the exposure…the

majesty would not be properly conveyed using a K2 [#8 yellow] filter…I saw the

photograph as a brooding form, with deep shadows and a distant sharp white peak against

a dark sky [1]." Waiting until mid-afternoon when the sun and shadows posed an optimal

balance, Adams shot the final with the #29 as a 5sec exposure at f/22. "This photograph

represents my first conscious visualization; in my mind’s eye I saw the final image as

made with the red filter. I was fortunate that I had that twelfth plate left…this was one of

the most exciting moments of my photographic career [1]."

"Monolith: The Face of Half Dome (c1927)" is an early predecessor to Adams’ more

polished and famous Yosemite works, "Clearing Winter Storm (c1940)" and "Moon and

Half Dome (c1960)." All three have compelling narratives from Adams’ point of view,

and form a progression of his creative process. "Monolith" is raw and evocative, and if I

had to choose, my favorite of the three. It is the first photograph in which Adams

successfully utilized a deep red #29 Wratten filter to blacken a bland sky and push the

contrast limits, taking advantage of a recent snowstorm and afternoon sun-induced

shadows. Adams reminisces about the 2500 ft. steep climb he made that day with his

fiancée and friends. He shot a total of twelve Wratten Panchromatic glass plates during

the climb, and was left with two when he turned to face the Half Dome at a famous high

ledge. Not satisfied with his first exposure, Adams prepared for his final. "I realized that

the image would not carry the qualities I was aware of when I made the exposure…the

majesty would not be properly conveyed using a K2 [#8 yellow] filter…I saw the

photograph as a brooding form, with deep shadows and a distant sharp white peak against

a dark sky [1]." Waiting until mid-afternoon when the sun and shadows posed an optimal

balance, Adams shot the final with the #29 as a 5sec exposure at f/22. "This photograph

represents my first conscious visualization; in my mind’s eye I saw the final image as

made with the red filter. I was fortunate that I had that twelfth plate left…this was one of

the most exciting moments of my photographic career [1]."